Law & Regulation

Party Politics Are Getting in the Way of Cannabis Legalisation in the UK

The trend towards decriminalisation and legalisation of recreational cannabis across the globe is snowballing. Have you noticed? In light of the growing…

The trend towards decriminalisation and legalisation of recreational cannabis across the globe is snowballing. Have you noticed?

In light of the growing body of evidence highlighting the medicinal uses of cannabis and the harms of punitive drug policy, this controversial plant is now legal in Uruguay, Canada and across a multitude of US states. European countries like Portugal, Malta and Luxembourg have decriminalised possession for personal use, while Germany’s plans to create a fully regulated legal cannabis market are underway.

While the UK legalised cannabis for medical purposes in November 2018, laws on recreational use remain some of the strictest in Europe, with cannabis possession punishable by up to five years in prison and an unlimited fine. And yet, the available evidence shows that legalising cannabis would: improve patient access to treatments; combat racial injustice; and boost the economy in this innovative billion-pound field, creating tens of thousands of jobs in the process.

The UK’s legal stance on cannabis is becoming more incognizant with contemporary research by the day. These considerations leave many wondering why the government isn’t engaging in the creation of evidence-based drug policy, announcing plans to decriminalise cannabis or legalise its use recreationally.

Quick recap: criminalisation perpetuates harm

As it stands, the criminalisation of cannabis creates huge social and economic costs which perpetuate harm.

-

Social and racial injustice

If the War on Drugs was waged to minimise harm, then it is a resounding failure. In fact, criminalisation increases the risks associated with substance-use because it fails to tackle its root causes. Instead, punishing cannabis users generates stigma which marginalises individuals with problem drug use and lessens the chance of successful recovery. While punitive sanctions are ineffective, they do push the cannabis market underground. Criminal business models can thrive and cannabis products cannot be regulated to maximise consumer safety.

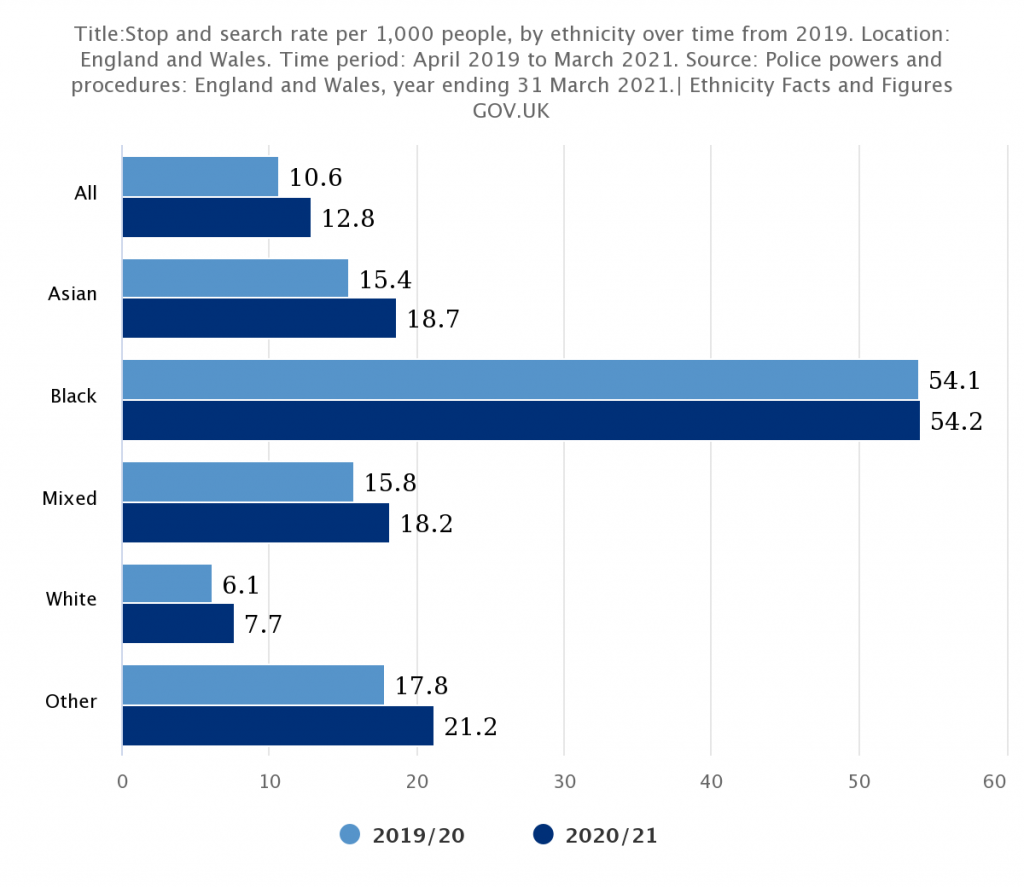

In addition to this, the racial motivations behind the creation of the War on Drugs are now well-documented. A 2018 report found that cannabis laws in the UK criminalise the Black community at disproportionate rates. Black people are nine times more likely to be stopped and searched than white people, despite being less likely to use drugs. BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Colour) individuals are more likely to be searched, prosecuted and convicted for cannabis offences. Sentencing is also harsher.

-

Resource allocation

Criminalisation is expensive. Given that it is also an ineffective rehabilitative tool, it is doubly damaging that all the resources spent on prosecuting, sentencing and imprisoning cannabis growers, traders and users are not available to treat and support those affected by problematic cannabis use.

Research shows that regulation – rather than prohibition – is the most effective pathway for addressing both the harms caused by criminalisation and the issues which can stem from substance use. Legalising cannabis would create the opportunity to restrict minors’ access to cannabis, increase consumer safety and tackle gang-related violence associated with the illicit cannabis industry.

So why isn’t the government doing anything about it?

Cannabis: a hot potato?

The 1980s and 90s saw the deployment of government-led advertising campaigns like ‘Just Say No,’ and ‘D.A.R.E’ (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) which claimed to discourage children from using recreational drugs such as cannabis, MDMA, and cocaine. Although the campaigns had no significant impact on recreational drug use, they had a paternalistic, scaremongering effect which created distorted perceptions of the plant and framed cannabis as a moral issue.

The 1980s and 90s saw the deployment of government-led advertising campaigns like ‘Just Say No,’ and ‘D.A.R.E’ (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) which claimed to discourage children from using recreational drugs such as cannabis, MDMA, and cocaine. Although the campaigns had no significant impact on recreational drug use, they had a paternalistic, scaremongering effect which created distorted perceptions of the plant and framed cannabis as a moral issue.

To this day the liberalisation of cannabis laws remains controversial among conservative voters. The 2018 Volteface cannabis poll found that younger populations are the strongest supporters of legalisation. This was also true in Canada, where legalisation was enacted in 2018 following the Liberal Party’s mobilisation of young and BIPOC voters. Meanwhile the Conservative Party’s core voting demographic is older populations, many of whom grew up during the height of the war on drugs hysteria. Despite the utilitarian benefits of cannabis reform, it is arguably not in the best interests of the party to consider reforming cannabis laws if they wish to secure the older vote at the next election.

Even the most tentative, evidence-led efforts by politicians to explore progressive approaches to regulating cannabis are met with moral outcry and hyperbolic headlines in the media. A localised, non-punitive cannabis education scheme proposed by Sadiq Khan in 2022 generated such a wave of misinformation and controversy that more than a dozen Tory MPs consequently called on Khan to block its development. This was notwithstanding strong public support and the successful implementation of similar schemes in other constituencies across the country.

The thorny politics of long-term policy

Another formidable roadblock on the path to UK cannabis legalisation is the farsighted style of governance that is required to appreciate its benefits. From the Conservative Party’s perspective, cannabis legalisation has, at best, mixed support among their main voter demographic and the tangible advantages of such a move may not be fully realised until the next election cycle.

Cannabis legalisation – alongside the creation of a regulated legal market – is a large and ambitious undertaking. The legal infrastructure it requires must comprehensively cover a range of core aspects including cultivation, manufacture, distribution, THC limits and advertising. While legalisation requires investment in the present, it could take years for the benefits of such a move to fully emerge. This presents a thorny issue in a governance system premised on constant competition for mass public approval.

To what extent do elected politicians invest in the future at short-term cost? Governments are faced with the need to strike an appropriate balance between maximising social welfare in the present and investing in future goals. However, the need for public support can maximise the value of short-term return at the cost of longer-term achievements. In this way what seems like a policy priority might not be politically desirable. This problem is not exclusive to the current government but is demonstrative of the intertemporal nature of the tradeoffs which take place in modern democracies.

Despite the overwhelming evidence supporting cannabis legalisation and some vocal, in-party support for cannabis policy reform, the structural and temporal limits of modern democracies makes long-term issues challenging to engage with. From a strategic standpoint, this conundrum engenders an aversion to taking positive action on controversial issues which the current government may not reap the rewards from.

Greener days ahead

Evidence-based advocacy is an important tool to shed light on the long shadow cast over cannabis as a result of the war on drugs. Increased awareness and the growth of the cannabis industry worldwide are mutually reinforcing factors aligning perceptions of the plant with the evidence available. Similarly, disseminating a more nuanced understanding of problematic substance use and the ways in which criminalising it is counter-productive will ensure lawmakers have the necessary tools to create effective, harm-reducing drug policies.

Despite decades of suppression cannabis remains the most widely cultivated, trafficked and used illicit drug worldwide. The fact is that it doesn’t seem to be going anywhere and the question regarding cannabis drug policy reform is not ‘if’ but ‘when’. The need to develop a political environment in which politicians are able to invest in long-term goals is a challenge to which modern democracy must rise in order to manage intergenerational socioeconomic issues like cannabis legalisation.

The post Party Politics Are Getting in the Way of Cannabis Legalisation in the UK appeared first on Volteface.

regulation laws research psychedelics mdma

-

Psychedelics7 days ago

Psychedelics7 days agoExploring Psilocybin’s Potential in Diabetes Management

-

Psychedelics7 days ago

Psychedelics7 days agoAll About the New Ketamine Trial at the University of Otago

-

Psychedelics1 week ago

Psychedelics1 week agoCybin to Present at the 2024 Bloom Burton & Co. Healthcare Investor Conference

-

Law & Regulation1 week ago

Canada’s Optimi Health to ship psilocybin to New Zealand psychedelics research center

-

Law & Regulation1 week ago

Law & Regulation1 week agoSynaptogenix increases psilocybin stake with PsygaBio

-

Psychedelics6 days ago

Psychedelics6 days agoThe EU’s Plan for a €6.5M Study of Psychedelics To Treat Mental Disorders

-

Psychedelics6 days ago

Psychedelics6 days agoThe EU’s Plan for a €6.5M Study of Psychedelics To Treat Mental Disorders

-

Psychedelics7 days ago

Psychedelics7 days agoExploring Psilocybin’s Potential in Diabetes Management