Psilocybin

The Forgotten Frontier: Why non-medical psychedelic use needs regulation

In the past few years, psychedelics have been attracting a lot more public debate and positive coverage. The so-called psychedelic renaissance has made…

In the past few years, psychedelics have been attracting a lot more public debate and positive coverage. The so-called psychedelic renaissance has made this fascinating group of drugs a mainstream topic of debate as their medical and therapeutic potential is increasingly becoming recognised.

For the past fifty years, psychedelics have been controlled under domestic and international drug laws – generally in the highest risk classification or schedules. But as debate around facilitating clinical and therapeutic access opens up, policy discussions around other using motivations have been marginalised, in particular the growing use of psychedelics in private and recreational settings, despite such non-medical uses constituting the majority of all psychedelic consumption. Transform’s new book How to Regulate Psychedelics: A Practical Guide aims to fill this gap in the policy debate by developing a set of proposals for regulating psychedelics outside of the medical sphere.

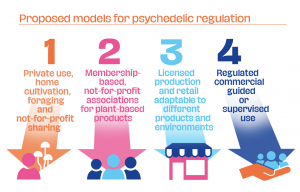

Before exploring regulatory models it is important to emphasise that ending the criminalisation of people who use any drugs (including, specifically, possession for personal use) is a vital precondition for any meaningful drug reform, including options for regulation. Moving beyond decriminalisation alone, we envisage a four-tiered regulation model, with the models operating in parallel, to accommodate the wide variety of ways people use different psychedelic preparations in different cultural/social contexts. We focus on the regulation of LSD, psilocybin, DMT and mescaline, sometimes known as the ‘classic’ psychedelics group due to the similarities in their effects and modes of action. However, we hope the proposals can inform thinking and potentially be adapted for other drugs with similar or overlapping effects and risk profiles. Our proposals are based on the principle that any risks associated with drug use and drug markets are increased under prohibition.

Model 1: Private use, including home cultivation, foraging and not-for-profit sharing

The consumption of psychedelics, as well as the cultivation and foraging of plant-based psychedelics, are behaviours that take place almost exclusively in the private sphere. While the state has a responsibility to provide health and risk information, private use would not be within scope of formal government intervention, which is generally neither practical nor justified given the low level of harm and intrusive nature of regulatory controls and enforcement regarding private use.

We propose a comprehensive decriminalised model which, in addition to possession for personal use, includes the removing of criminal sanctions for:

- Foraging (excluding, peyote and other endangered or protected species, where it is relevant);

- Small-scale cultivation;

- Small-scale, not-for-profit sharing.

Model 2: Membership-based, not-for-profit associations for plant-based products

This proposal is modelled on the cannabis social clubs pioneered in Spain since the late 1990s. Personal possession and cultivation allowances established under Spain’s existing decriminalisation approach were expanded – through an iterative series of legal challenges establishing case law – to include collective growing and sharing among adult members within the not-for profit-clubs. Such associations, since adapted and formalised in the legal cannabis models of Malta and Uruguay, bring specific benefits to members who get access to a legal quality controlled supply within a safe community-based environment, whilst avoiding the pitfalls of some profit-motivated commercial models. Similar associations for plant-based psychedelics (likely focusing on Psilocybe mushrooms) would be licensed by a regulatory authority to ensure they adhere to licensing requirements including on membership limits, product controls, and training requirements.

Model 3: Licensed production and retail of psychedelics

The relatively low levels of risk associated with most psychedelic use places them nearer to cannabis in terms of regulatory thinking on possible retail models. We have proposed that specific psychedelic products from licensed producers could be sold to adults in licensed physical or online outlets. Trained vendors would be required to provide safety and harm reduction information at point of sale including on, for example, dosage, effects, risks for certain individual vulnerabilities, contraindications with prescribed drugs, and so on. Marketing and advertising would be restricted in a similar fashion to tobacco in the UK, while packaging would remain functional, focusing on providing content and safety information.

Model 4: regulation of commercial guided or supervised use

Where psychedelics are administered by one individual to another, or to a group, in some form of supervised or guided experience that is being provided commercially, regulatory oversight will be necessary. This would require a regulatory authority to oversee the: training and accreditation process of prospective supervisors/guides; licensing of venues; and establishing best practice guidelines including screening of participants, safeguarding issues, and provision of emergency care. As with licensed retail, there would be restrictions on marketing and promotion such as making medical claims.

Embedding social justice and equity in emerging regulatory models

Emerging legal drug markets are an opportunity for policymakers to be ambitious and to do things differently and better as they develop the regulatory frameworks – learning from mistakes made with alcohol and tobacco regulation as well as from the positive innovations we have witnessed in legal cannabis markets. Embedding principles of social justice and equity should be at the heart of policy thinking, principles that have been too often absent or undermined both in unregulated illegal markets and inadequately regulated legal markets.

A strong political commitment is needed to uphold these principles in order to avoid risks of replicating the inequities of prohibition in emerging markets. As has been seen in debates around cannabis legalisation, people from marginalised and racially minoritised communities risk exclusion from policy making decisions, as well as facing barriers to participation in emerging psychedelics markets. We have identified several policy elements that can work together towards achieving social justice and equity goals.

Within the commercial sector, using licensing tools to ensure a diverse market landscape populated by small and medium sized businesses will be essential in mitigating the risks of market consolidation, the emergence of monopolies, and regulatory or corporate capture – that can distort policy towards the interests of corporate profits rather than the wider public good. Mitigating these risks should include limiting the number of production and retail licences available to one entity and also preventing licences to companies which may have a disproportionate existing advantage in entering the market such as the medical psychedelic industry, or companies involved in other large-scale drug production or retailing, most obviously alcohol and tobacco industry actors. Inclusion of not-for-profit market models such as decriminalised private cultivation with not-for-profit-sharing and membership-based associations will be an important component of mitigating risks of over-commercialisation and corporate capture.

A second element of a social justice oriented approach is implementing equity programmes which facilitate and empower historically marginalised and impacted communities to meaningfully participate in, and shape, policy and regulatory frameworks. Psychedelic reforms should look to lessons and emerging best practice of community-led equity programmes in emerging cannabis markets. To be successful they should include: reducing or removing financial barriers for equity applicants such as application and licensing fees (and any other associated costs), prioritising equity applicants in the licensing process, and offering technical assistance and wraparound benefits, including legal and account services, and workforce and development training.

It is grimly ironic that the emerging psychedelics market — making claims to heal trauma, and now able to open up as the end of so-called the war on drugs edges closer — is potentially excluding populations who have been most traumatised by the brutalities of the war on drugs. It is important to ensure access to market participation — including supporting diversity among licensed supervisors/guides, as well as affordable access to therapeutic/wellness services — whether operating within formal clinical settings or not.

A third element is to secure the right of religious and Indigenous communities to freedom of belief and practice regarding traditional use of psychedelic plants, and to ensure it is not encroached upon by regulatory frameworks for other forms of access such as retail or commercial supervised use. As these communities risk being some of the most impacted by an emerging psychedelics market, it is important that cultural sensitivity and reparatory justice for Indigenous communities is central to relevant psychedelics policy reforms. These communities, whose practices have been undermined, stigmatised and, in many cases, criminalised, now risk being exploited and appropriated. There are some protections that formally exist at UN-level but they are inadequate, making state-level exemptions and protections necessary – of which a number already exist in the US and elsewhere. Such policy needs to be nuanced and Indigenous led. Opportunities for justice include benefit sharing, where corporations give a portion of their profits -or a share in other advantages gained by policy reform – from the use of genetic resources or traditional knowledge to Indigenous communities.

The surging interest in psychedelics brings opportunities and challenges for policy making, civil society and business. We hope that Transform’s new guide can usefully inform the often marginalised policy debates around non-medical use by making coherent and considered proposals that cater to the different patterns of consumption, and centring concerns around public health and social justice, without neglecting the need for responsible regulation of commercial actors in emerging markets

How To Regulate Psychedelics: A practical guide is available as a free ebook on Transform’s website, or you can order a print copy here.

The post The Forgotten Frontier: Why non-medical psychedelic use needs regulation appeared first on Volteface.

psilocybin lsd dmt peyote mescaline regulation laws psychedelics psychedelic

-

Law & Regulation1 week ago

Law & Regulation1 week agoClearmind signs agreement with Hebrew University for psychedelic compound rights

-

Psychedelics1 week ago

Psychedelics1 week agoCybin Announces Publication of Research Manuscript in the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry

-

Psilocybin1 week ago

Psilocybin1 week agoCalifornia advances bill for psychedelics centers

-

Psychedelics1 week ago

Psychedelics1 week agoPsychedelics Can Offer More Than Therapy On Its Own

-

Psilocybin4 days ago

Psilocybin4 days agoPassover Perspectives: Psychedelics, Moses, and the Burning Bush

-

Psychedelics1 week ago

Psychedelics1 week agoRevive Therapeutics Announces FDA Acceptance of Meeting Request for Long COVID Diagnostic Product

-

Psychedelics3 days ago

Psychedelics3 days agoAlgernon NeuroScience and the Centre for Human Drug Research to Present DMT Phase 1 Stroke Clinical Data at the Interdisciplinary Conference on Psychedelic Research June 6 – 8th, 2024

-

Psychedelics4 days ago

Psychedelics4 days agoRevive Therapeutics Announces Type C Meeting Request Granted by FDA for Clinical Study of Bucillamine to Treat Long COVID